“We do not do projects anymore, only experiments.” – Barry O’Reilly

John, the Product Owner of the Plymouth Team, was confident about the new release of their product: an app for truck drivers to know when and where they have new loads when returning from a trip. For many years, the company phoned the drivers to achieve this. According to John, “mobile first is the new revolution.” The support call center was well trained to help the drivers. So what could be wrong?

After a while, they discovered many truckers could not use the new app; they had old phones with no internet to use on the road. Truckers just ignored the app and phoned back to base. John’s assumption was flawed.

Our past experience influences, but does not predict, the future. It is important to have previous experience on the product’s domain. However we cannot guarantee future user behaviours. So even a well-defined requirement ready to be developed in a product is an assumption that must be validated. Not just through acceptance testing, but from the end user on the real workflow.

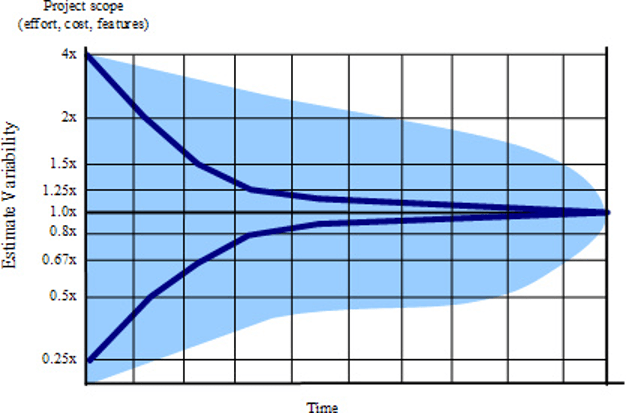

If the project is not well controlled, or if the estimators aren’t very skilled, estimates can fail to improve as shown by the Cone. It shows what happens when the work isn’t conducted in a way that reduces variability – the uncertainty isn’t a cone, but rather a cloud that persists to the end of the work. The feature is only done when the end user is properly being benefited from the respective work. Their behaviour has changed in some way, meaning the outcome can be observed as part of our Three-Stream learning loop.

Belief-Driven Development

Belief & Evidence in Empirical Software Engineering, the name of the study made on large projects in Microsoft (Prem, 2016), showed us the incredible conclusion that personal experience is the most important factor on forming opinions:

“Programmers do indeed have very strong beliefs on certain topics, their beliefs are primarily formed based on personal experience, rather than on findings in empirical research, and beliefs can vary with each project, but do not necessarily correspond with actual evidence in that project.”

That’s what we call “Belief-Driven Development”, the opposite of a data-informed mindset. We have a natural belief system since we are human. But we can’t let our egos decide where the product will go without data for validating learning. We can believe in something, but treat it as a hypothesis to be proved (or not).

Pattern: Hypothesis-Driven Development

“We consider it a good principle to explain the phenomena by the simplest hypothesis possible.” Ptolemy (c. 100 – c. 170 AD)

It’s just a supposition when we think of a need from the user, even if they told us their needs directly. A proper validation happens only when and how the end user behaves in using the feature, generating a result. Have the mindset that every problem or proposed solution is a hypothesis, even if we have a solid market fit. Not just for new products or new features, but every change or improvement made.

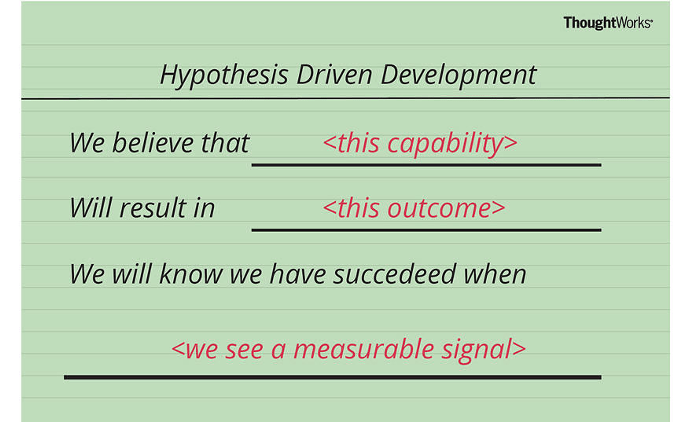

Choosing the right metric is key – perhaps as key as the idea to test itself! A way to help choose the right metric is by using a Hypothesis Template. It looks like this:

The measurable signal is observable as part of our Three-Stream learning loop, informing us if the assumptions we’re testing in the market are correct or incorrect, based off qualitative or quantitative feedback. We would recommend using this template to replace standard epics in your product backlog.

Reviewing your hypothesis statements in the Third Stream

After you have created your hypothesis statement in the First Stream you will likely have done some lightweight testing of your assumptions using a prototype. However, many product teams stop using it there. We recommend taking it a step further after you’ve shipped your feature in the Second Stream. In the Third Stream, revisit your original hypothesis statement regularly, and review the measurable signal you defined earlier against actual live production data.

This review should be baked into your existing rituals, such as your Sprint Reviews, for example. This could be reviewing the results of an A/B test, for example. Remember, although prototyping is very valuable, it is not until the Third Stream until you truly validate your assumptions with real users in a real-life environment.

Moreover, we also recommend to take a look at the canvases from Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden’s book, Lean UX. In the book, they share a nifty tool called the Lean UX Canvas, which we have found a great technique to help the whole team gain shared understanding on user and business outcomes, as well as how to test our hypotheses.

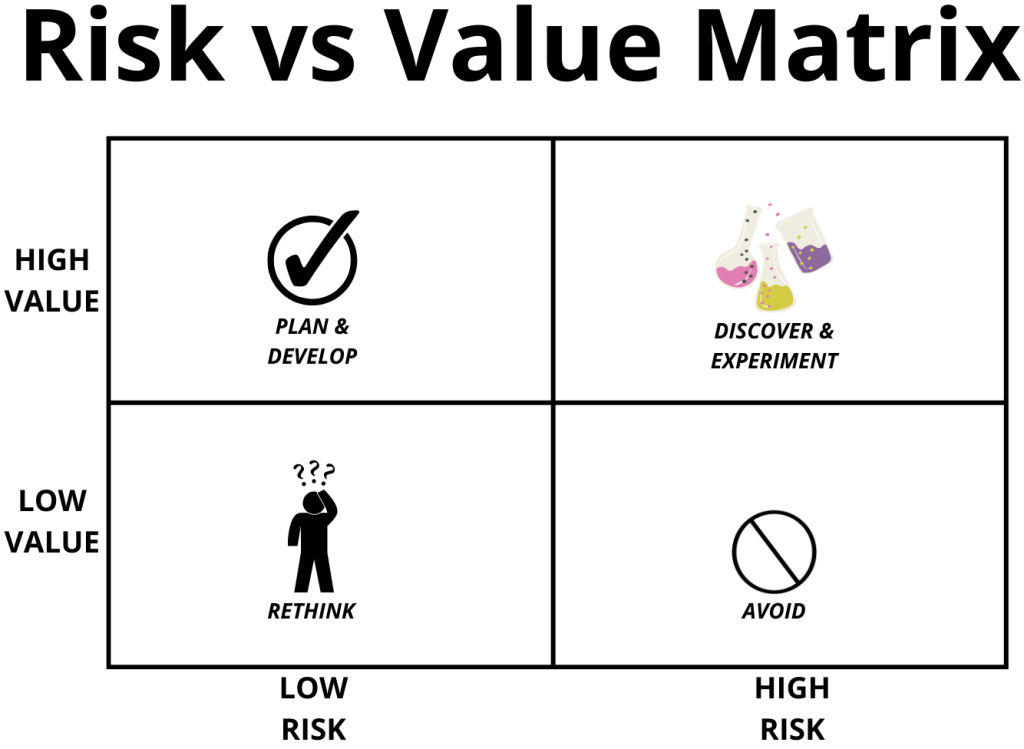

Last but not least, since we will have too many hypotheses to test, we must categorise and prioritise them. The Risk vs Value Matrix may help:

For that, take account there are four types of risk, according to Marty Cagan (2017):

- value risk: will customers buy it? will users choose to use it?

- usability risk: can users figure out how to use it?

- feasibility risk: can our engineers build what we need with the time, skills and technology we have?

- business viability risk: does this solution work also for the various aspects of our business?